Analysis: Is it ethically justified to have children?

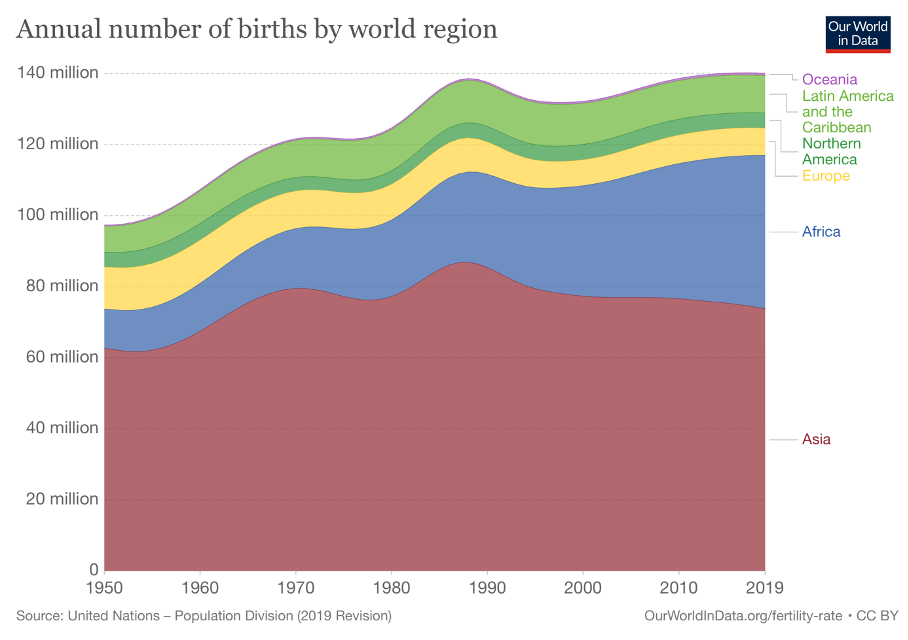

We are all aware that ice caps are melting, rainforests are being felled or burned down, and the ozone layer is depleting. The number of conflicts in the world is increasing. Relative poverty is growing. The world economy could look completely different after the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, over the years these kinds of crises never stopped us from reproducing. With the global birthrate increasing from 132.21 million in 2000 to 140.11 million in 2019, the global average fertility rate is just below 2.5 children per woman today. What influence does this number have on global challenges that we encounter today? Should we be wondering whether or not it is ethically justified to be having these amounts of children?

First of all, let us look at how the global birthrate is divided around the world. Statistics show that the vast majority of children are born in Asia and Africa. There are various explanations for this. First of all, children are often needed to work and bring in an income for the family. They are also required to look after elderly parents because of a lack of pensions and healthcare. In addition, African and Asian countries are signed by high infant mortality rates. In order to deal with that, parents tend to have more children hoping that some will survive. Religious beliefs can also be a cause, and lastly, developing countries often lack availability and knowledge of contraception and family planning. Now, this is nothing new. However, what is new, is the question of whether or not the rest of the world is partially responsible for the birthrate in these continents. Other, wealthier, world regions should be investing in birth control and other programs to tackle (at some places even increasingly) high birth rates.

It is well-known that overpopulation is a major challenge and that global issues would be much easier solved if the global population were to be smaller. Yet, many people consider this to be far removed from their own personal lives. They think that they don’t have to think about it, don’t have to take it into consideration. Nothing is further from the truth, as parents leave the world that humans have so far created to their offspring. They have to cope with problems that we have already encountered and failed to resolve. The children and grandchildren of Generation Z (people born between +- 1998 and 2015) might perhaps experience a third World War. They might encounter robotization of things that we cannot even begin to imagine today, and scientists are already sure that they will experience negative long-term consequences of climate change. It does not hurt to wonder now and then if this is a world you want to leave to your (future) children.

However, as social psychologist William MacDougall concluded, people have a certain reproduction instinct. There is a reason that many languages have similar sayings about the urge to procreate descendants; it is a major part of the purpose of mankind. Although this instinct can vary greatly in time and place, it is nonetheless present in each individual human being. Thus, it is inhumane to prohibit or actively discourage people from having children with the aim of bringing down the worldwide birth rate.

Well then, how do we approach the phenomenon of overpopulation in a humane, sustainable and peaceful way? The key is education. Inform people around the world about reproducing and what it means to have large numbers of children. Educate people about contraceptives and develop campaigns that encourage having two kids, for instance. With this positive approach, people will be able to choose for themselves how to limit their number of children. Luckily, this approach has already been established on multiple continents, but it should be implemented even broader and wider around the world.

All in all, overpopulation is a global challenge and not a local one. It is no longer acceptable for rich, developed countries to bury their heads in the sand and pass the responsibility to Africa and Asia. We should unite and tackle these global issues together.

By Myrthe Egberink