(Review) Orhan Pamuk: history, politics, and melancholy in modern Turkey

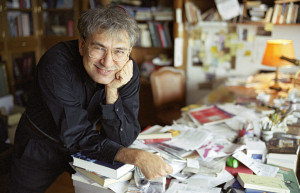

Studying scholarly facts-based history can sometimes elude us from understanding human experience in terms of feeling and emotion. We can often escape from the dangers of this (potentially) alienating experience by supplementing the study of classical accounts of history with other non-scholarly sources: historical fiction, memoirs, diaries, etc. In the current cross-cultural debate, one can find valuable insights in the work of Turkish writer, academic, and 2006 Nobel Prize winner, Orhan Pamuk, ‘who in the quest for the melancholic soul of his native city has discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures’, in the words of the Swedish Academy.

Orhan Pamuk was born in 1952 into a secular upper-middle-class Istanbulite family and educated in Western-oriented Turkish élite schools. From an early age he prepared himself to devote his life to painting. However, at the age of 22, he dropped out from the university to become a full-time writer (an experience described in his 2003 memoir Istanbul: Memories of a City). He spent the next eight years working assiduously ten hours a day to become a writer, debuting in 1982 with Cevdet Bey and his Sons – a family chronicle stretched over a period of three generations written in the classical tradition of Thomas Mann and John Galsworthy. Since then, he became a sensitive painter of words that writes a highly visual, sensory, and insightful prose devoted to the problems of identity, plurality, memory, cultural clashes and fusions, all pervaded by a sense of tenderness and melancholy that emanates through most of his best pages.

His second novel, The Silent House, captures the atmosphere of the 1980 Turkish coup d’etat in a story told from several parallel perspectives about a dynastic reunion that bifurcates into a set of sub-themes, such as the parochial family and inter-generational tension. The third novel became Pamuk’s first international success. The White Castle is a historical novel set in the 17th century Istanbul about the interplay of identities of a Venetian and an Ottoman young scholar who by telling their stories exchange their identities, bridging the cultural divide. The play with identities, doubles, and the ambiguity of the self are recurrent themes in Pamuk’s work.

His next novel, The New Life, describes the irrevocable impact a book can have on our lives, becoming not just a simple extension of the mind, but a separate organ of our anatomy that subjugates us, acquiring the status of a devouring obsession. Such a ‘total’ book enraptures the protagonist, triggering a marvelous and mystical odyssey in search of the lost self across the modern Turkey. In 2002, Pamuk published My Name is Red – a multifaceted journey through the sumptuous Ottoman court set in the XVIth century, designed to recollect the puzzles of the glorious times of the Ottoman Empire through a kaleidoscopic narrative that mixes philosophical debate, East vs. West approach to the meaning of art and the role of the individual in the artistic enterprise, but also touching on a wide range of other subjects, from power and religion to sex and crime.

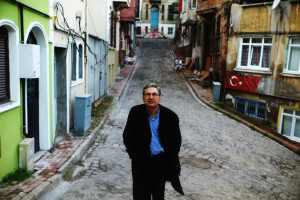

As with My Name is Red, most of Pamuk’s novels are set in Istanbul – “the name of a city and the name of an illusion”, as Elif Shafak put it. For the readership community of Pamuk’s work, Istanbul acquired that iconic status that equalizes the mythical image of Dostoyevsky’s Sankt-Petersburg, Proust’s Paris, or Joyce’s Dublin. Pamuk has lifted from the waters of Bosphorus a fastidiously constructed revived image of Istanbul – a phantasmagorical city of melancholy and elusive past -, composing its spiritual biography as a polyphonic construction made up of the voices and stories of his characters. In his works, the physical reality of Istanbul – its intricate cobweb of streets, painterly walls, sulphurous sunset light, pale streetlamps, vaporous voices in the night -, becomes the arena of intricately plotted narratives that straddles the intersection of the classical (and often prejudiced) dichotomy of East and West.

As with most public figures, Pamuk has a reputation divided between harsh criticism and wide acclaim. Some literary critics have attacked him for supposed deficiencies of style and bizarre language (a phenomenon mostly referred to the original texts, the translations being meticulously polished), a occasionally schematic representation of the characters, or what some see as a thematic provincialism in some of his earlier works, that didn’t appeal to the foreign readers. Nethertheless, as a novelist, Pamuk is a master: a storyteller, teacher, and enchanter all at the same time. However, in Turkey his reputation remains controversial, where he was trialed years ago for “denigrating Turkishness”, when he publicly condemned the Armenian genocide, repeatedly denied by Turkish authorities and its allies. At that time, a wide global solidarity of intellectuals put a substantial public pressure and the accusations were finally dropped, but Pamuk still represents a voice of dissent in Turkish society and much of the criticism about his work as a novelist is often motivated by the messages he diffuses as a public intellectual.

Last year Orhan Pamuk published a new novel, A Strangeness In My Mind: an affectionate, and episodically despairing, textual canvas that portrays the daily existence of the lower Istanbul social strata, but also a praise of the ordinary (and highly revelatory) life of those struggling for a living in the modern Turkey. Once again, Pamuk has proved that he has those mysterious devices able to enrapture a worldwide audience, guiding his readers in the exercise of deciphering Turkish identity – its Islamic roots and secularist modern system -, the sense of “Otherness”, but also the oddities of what does it mean to be alive. “The art of the novel, Pamuk says, is the skill to talk about yourself as you would talk about ‘other’ and about the ‘other’ as if you would talk about yourself”. Pamuk is a master of contemporary storytelling, and like a modern Scheherazade, as long as he’s alive he will have a story to tell.