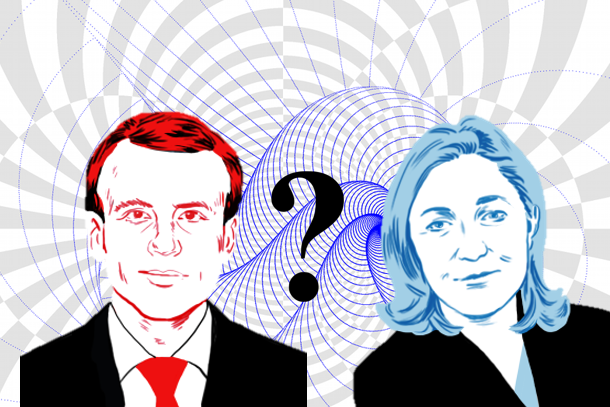

An Equation with Two Unknowns – How the unconventional 2017 presidentials brought about insecurity and hope

For several decades, the French presidentials have been one vested in traditions – From the different party preliminaries to the massive meetings in the weeks before the first round of the presidentials. At first glance this year’s French elections did not seem to make up for a very different campaign. However, when the all too common countdown moment was set on the biggest TV channel in France, TF1, there seemed to be this very brief moment of uncertainty and excitement that had disappeared for a long time from French politics. Recent poling had shown that the frontrunners in the presidential campaign were by that time Macron, le Pen, Fillon and Mélenchon. Only one of the four previously mentioned candidates represented a party from the classic party politics which reigned over France for many years. The others all represented political movements that, until that moment , had not been able to break the traditionalist structure of French politics. Their entrance into the mainstream politics proved to be a first movement indicating an abrupt change in French politics. With the ultimate coming about of a second round run-off between Emmanuel Macron and Marine le Pen, the French elections ultimately seemed to break with its traditions on an unprecedented scale. But what kind of future will it bring about for the Fifth Republic?

‘Une equation à deux inconnues’, an equation with two unknowns, said French magazine le Temps on the eve of the first round of the French presidential elections. It might not have been the second place of Marine le Pen but rather the implications of this year’s elections on the French political system as a whole that will stick in the mind of the French for a long time. Since its establishment in October 1958, the Fifth Republic of France had been governed by mainstream political parties that were strongly associated with the political spectrum of right and left wing politics. For many years right-wing Républicains and left-wing Socialistes ruled the country, president Hollande being the latest addition to a long list of French leaders. What is certain however is that the future president of France, whether that might be Emmanuel Macron or Marine le Pen, will break with this tradition of well-known traditionalist parties ruling the country.

The first contender, Emmanuel Macron has remained largely unknown to the general public until a few months ago. Leading his own political ‘En Marche’ movement, the former minister of Finance has gained widespread media coverage and attention. Calling himself neither right nor left and advocating further strengthening of European cooperation and integration, the former Rothschild banker has shown that it is very complicated to place him on the traditional political spectrum. Marine le Pen, on the other hand, was for a long time expected to make it to the second round after building up gradual momentum since her ascent in the polls starting back in 2012. With le Pen entering the second round, France took a path that it only took once in the past when in 2002 le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie le Pen, took his Front National to the second round run-off. An event which was, back then, perceived as a great shock to French society ultimately leading to a very large mobilization of all parts of the political spectrum behind, back then, Jacques Chirac from les Républicains. In 2017, however, le Pen’s success is being perceived as much less of a shock. Presenting a more humane and dignified face than her father, Marine le Pen has managed her way into mainstream French politics. It thus seems that the potential presidency of one of the two aforementioned candidates will prove to be a great shift that will undoubtedly cause to shake the Fifth Republic to its very foundations like it has not been shaken in a long time. Adding up to this is the unexpected surge of candidates like Jean-Luc Mélenchon, an extreme left politician advocating the establishment of a 6th Republic. In the 2012 elections, Mélenchon also ran and won roughly 11 percent of the votes. This year, that amount had increased to 19 percent. Due to this division on the left, socialist party candidate Benoit Hamon lost big and the traditional left was washed away by a new movement of extreme left tendencies. Classical left and right wing politics was thus replaced by a growing political centre and the rise of extremes.

The political climate in France is thus drastically changing but it is not the only factor of uncertainty within French borders. While le Pen and Macron differ greatly as regards their political points of view, they also have something in common that is, there is relatively little information nor knowledge about what a Macron or le Pen presidency would look like. For many years presidents were expected to push through the political stance of the parties they originated from, usually being the socialists or the republicans. However, with the old party structure and division collapsing, the future president does no longer seem to be bound by a real ideological stance. This opens up opportunities but also creates insecurity about which path France is likely to take. Whereas Macron has drawn extensively on his belief in the European project, he has spent relatively little lines on domestic issues. And for le Pen, a rejection of the European project has not yet been connected to specific consequences once she would become president, leaving doubts residing on whether a Frexit would actually see the light under a le Pen presidency. Such insecurity thus proves to be an extension of this year’s election’s predictability leaving the French but to wonder what might be up for them next.

Ultimately, there also resides a lot of doubt as to what extent the future French president will be able to unite his/her people once in office. With a French electorate torn apart by a highly fragmented political spectrum, their choice is now between two candidates that are in many ways each other’s opposites. No matter who will come out as the winner next Sunday, he/she will have a hard time in shaping a French nation of unity, in which the president finds sufficient support. The French elections thus draw on a recent European tradition of extremes, where the middle ground between them is gradually collapsing.

In an election year unlike any other, the presidentials seem to be only the first obstacle in a long chain that the French need to overcome if they want to ensure stability not only for themselves, but for the European continent as a whole. After next Sunday, there will most probably be only one path left to that future.