Death of a Democratic Commodity: Ambivalent, Kenya Mourns Daniel arap Moi

Nairobi’s Nyayo National Stadium rarely serves as a venue for state funerals. Indeed, the home of Kenya’s AFC Leopards is far from the customary cathedrals, boulevards and grand auditoria that transform into shrines where mourning nations pay respects to their deceased leaders. Yet on February 11th, the stadium became just that. The leader in question was Kenya’s longest-serving president, Daniel arap Moi. Having led an island of stability in an otherwise troubled region, Moi’s complex legacy has resurged as the rhetoric surrounding his death equates his passing to the loss of a national hero. While Moi did not defy constitutional limits on presidential terms, a rather unique gesture in the region, what preceded a relatively fair transfer of power is anything but democratic. As Kenya mourns Daniel arap Moi, uncomfortable realities of his leadership resurface among a predominantly lionising national mood.

Toroitich arap Moi was born in 1924, initially training as a teacher and adopting the name Daniel during his education at a Christian missionary school. In 1955, he was elected a member of the legislative council for Kenya’s Rift Valley. In 1960, he founded the Kenya African Democratic Union as a centralist force opposed to the federalist tendencies of Jomo Kenyatta’s Kenya African National Union, only for the two parties to merge in 1964 after Kenya attained its independence from the United Kingdom. In 1967, Moi was promoted to vice-president after initially serving as minister of home affairs with close support of his former political rival. When Kenyatta died in August 1978, Moi assumed interim presidency in full accordance with the Kenyan constitution, though a Special Cabinet meeting held shortly after declared new elections unnecessary. Thus, Moi was sworn in as Kenya’s second president in August 1978. After a series of power-consolidating measures, five semi-free elections were won by the president.

Moi’s lionisation is not without a reason. He was a man of the people, gaining support due to his approachability while touring the country. In contrast to its predecessor, the Moi regime was able to achieve an initially high degree of national unity. The president attempted to revitalise the tourism and agricultural sectors of the economy, while gaining further popular support with his free milk for children scheme. Yet, despite critical voices pointing to Moi’s subsequent dictatorial practices, the political elite of the mourning nation seems to have forgotten many of the former president’s abuses of power. This is surprising, as prior to his constitutionally-mandated departure from office in 2002, these were a common occurrence.

If Moi the unifier was a hero, Moi the dictator was far from benevolent. His power as head of state and government was virtually unchecked. A failed 1982 coup d’état attempt by a group of air force officers and university students critical of Kenya’s status as a de-facto one party state provided the president with an excuse to eliminate much of his political and civil opposition. Persecution of political opponents was often overlooked, as in the context of the Cold War, Moi’s anti-communism provided good reasons for much of the Western world to turn a blind eye to such transgressions. Several corruption scandals occurred during Moi’s rule, costing Kenya hundreds of millions of pounds and turning the country into a land of economic and societal dichotomies.

His transgressions notwithstanding, Moi’s funeral was marked by a rhetoric of icon-formation. Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Moi’s predecessor and current president of Kenya, sketched the former president as “one of Africa’s greatest, a man who made his nation and the continent immeasurably better.” Thus, a longer-term tendency in Kenyan politics was confirmed. As the Kenyan anti-corruption journalist John Githongo remarked in a 2003 interview, “Moi is an important democratic commodity, not only for us but for Africa. He is treated special. He is different. He’s just not any other guy.”

While Kenya’s upper echelons praised Moi at the Nyayo National Stadium, a lone protester was swiftly removed by security forces after interrupting a speech. Meanwhile, the Kenya Television Network’s de-facto monopoly on the broadcast of the former president’s funeral was criticised by many of the country’s independent media outlets.

It is important that Githongo’s quote is not interpreted as yet another teardrop in the ocean of Moi’s lionisation. Indeed, Moi was no “any other guy” to Kenya’s political elite, since he practically enabled Uhuru Kenyatta’s political ascent and covered the wealth amassed by the current president’s father. The elite’s praise for the despot is thus nothing but an expression of gratitude. But perhaps it is more than that, for Githongo’s assessment also placed Moi’s legacy in the broader African context. As a “democratic commodity,” Moi built upon the work of Jomo Kenyatta in securing Kenya’s role as an independent, stable and regional leader in East Africa. His respect for a constitutionally-mandated departure from office is also a rare, yet welcome example for other leaders in the region.

However, Moi’s maintenance of Kenyatta’s legacy in asserting his country as a postcolonial state is perhaps of the greatest importance. To a community of nations marked by a common history of subjugation, this claim of identity-affirmation is paramount. In light of this claim, Moi’s transgressions become mere symptoms of fallibility. It is a similar trend to that observed in Ghana with the persona of Kwame Nkrumah, or in the case of Nigeria’s Olusegun Obasanjo, to cite a few examples. Ambivalent, Kenya continues to mourn. Moi’s legacy, however complex, nevertheless illustrates that postcolonial legacies continue to figure in domestic politics of African states, perhaps more than they do in their relations with former colonial powers.

Suggested Further Readings:

A New York Times article providing an overview of Moi’s complex legacy: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/03/obituaries/daniel-arap-moi-dead.html

An African Arguments article delving deeper into the reasons why Kenya’s political elite tends to lionise Daniel arap Moi: https://africanarguments.org/2020/02/12/kenya-performance-mourning-moi/

A France 24 ‘Across Africa’ video, which summarises the latter stages of arap Moi’s state funeral: https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20200213-a-complicated-legacy-kenya-s-longest-serving-president-dies-at-95

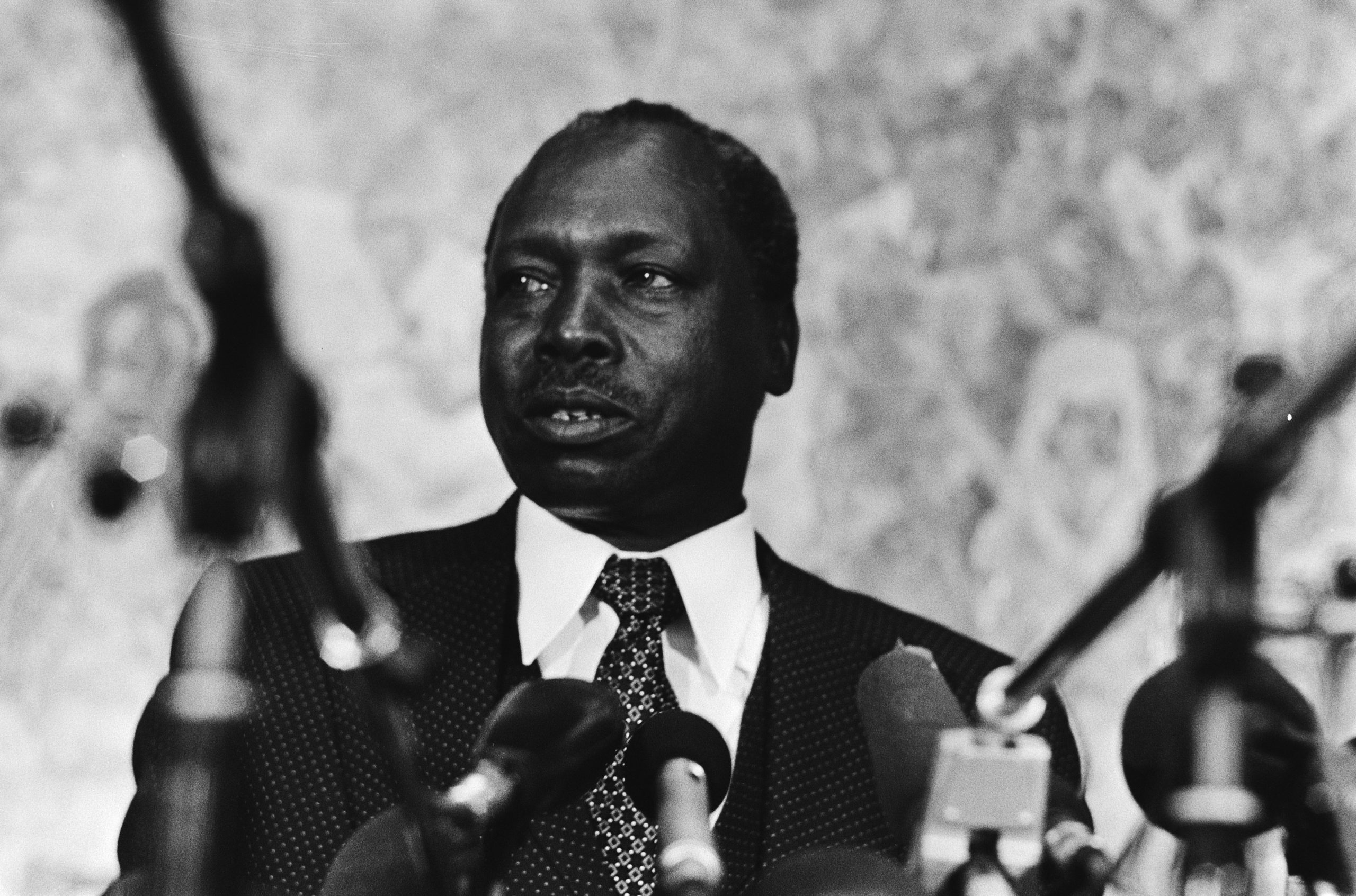

Featured Image:

Rob Croes / Anefo (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Presidenten,_persconferenties,_portretten,_Bestanddeelnr_930-3254.jpg), „Presidenten, persconferenties, portretten, Bestanddeelnr 930-3254“, https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/legalcode